The power of four

by Roger Lyons

It started with the realization, as the four of us were talking pedigree in the Keeneland lounge during the 2013 November sale, that each of us has a distinctive approach to figuring out what stallions are most suitable for the broodmares of our respective clients. And, I might add, while open-minded enough to be interested in alternative approaches, each of us is fairly hard-headed about the distinctive approach he takes, in no small part because the main reason why each of us is retained as an advisor to certain clients in the first place is that the respective programs of those clients are structured in a way that demands precisely that approach.

But what about the breeder who operates on a small scale, who has a small broodmare band, maybe just one or two, and who doesn’t have a highly structured program? What kind of approach does that breeder require?

It was Bill who came up with the idea of offering an individual mating analysis that would incorporate our four different perspectives into consensus stallion selections, tailored for the breeder who doesn’t have a cadre of advisors on retainer. None of us could have imagined how that idea would turn out in actual practice.

It’s interesting that, while Sid and I work together for clients of Werk Thoroughbred Consultants and Bill and Gary work together for their clients, our respective approaches allign quite differently. Gary and I both focus in our different ways on statistical-empirical answers to the question of compatibility of mates while Sid and Bill gravitate toward the pragmatics–pedigree potential and type, commercial appeal, racing opportunity, return on investment, and the purposes of the client. So, all four of us began the project already acquainted with the benefits of balancing perspectives.

Each of us nominates the stallions he thinks the client should consider, backed by a written argument in support of those nominations. Each of us reads the arguments of his colleagues. Then we vote on the order of preference for each of the stallions that have been nominated. Together with written arguments and supporting materials, we assemble the results into a report and deliver it to the client.

After we had set this project in motion last year, we were all surprised to find how non-competitive the consensus process turns out to be. The final analysis looks less like majority rule than fairly close consensus–agreement–as to the order in which we rank the nominated stallions. The only possible explanation is that an emergent argument arises from these four perspectives, an argument that could not have been made by any of the four of us individually, but that we all recognize as the most compelling argument.

That’s why it’s the most expensive mating analysis in the business.

Posted by Roger Lyons on Monday, September 8, 2014 at 4:25 pm.

• Permalink • Comments Off on The power of four

Notable Broodmare Sires of Sires

by Roger Lyons

Predictions about the potential of a newly retired stallion focus on three main pedigree topics–his racing career, the reputation of his sire, and the reputation of his female family. True, highly successful stallions do tend to represent excellence in these three areas. The problem is that most highly qualified stallions do not become highly successful sires.

Clearly, other important variables, either unrecognized or neglected, separate sires that become highly successful from other stallion prospects. One ancestor that does not get the attention he deserves is the stallion’s brodmare sire. The sire of a stallion’s dam is the second-most important sire in his ancestry, and the possibility that this ancestor could have an important, even a decisive, role is worth considering.

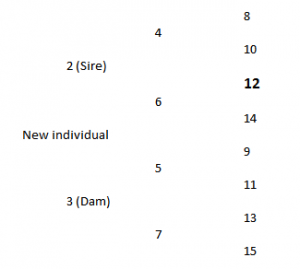

Position 12

The diagram below locates the sire’s broodmare sire in position 12 of an ancestry tree, as I number the positions:

This method of numbering the positions of an ancestry might seem idiosyncratic at first glance, but, if you put yourself in the place of a computer, which lacks your intuitive sense that an ancestry represents a series of genetic relationships, then its advantages become apparent. This numbering method reduces the genetic relationships in the ancestry to a small set of arithmetic functions that are constant throughout the ancestries of sire and dam, respectively. This means that the location of all genetic relations to a given node of the tree (the parent with which it is associated, its gender, its sire, dam, and immediate offspring) can be deduced arithmetically from the number of that node. For this reason, 12 is the natural number for the broodmare sire of the sire–at least, as far as a computer is concerned.

Another value of numbering the positions is that it provides a convenient shorthand reference, in this case position 12, or p12.

The tables accompanying this article list 58 notable sires, selected by means of a measure of their effectiveness as p12 sires. A p12 sire’s broodmare-sire-of-sires index (BSSI), featured in the tables, is obtained by surveying stakes winners by the individual sires representing a given p12 sire. For example, Great Above is the p12 ancestor of sires Housebuster, Myfavorite Place, Friendly Lover, Frisco View, and My Favorite Dream. These five stallions have sired an aggregate of 45 stakes winners. Since our index is intended to measure the effectiveness of the p12 ancestor, it is less concerned about the individual merit of those five sires than about their central tendency as a group. So, we divide the aggregate number of stakes winners accountable to them by the number of sires to get the average stakes output per sire, which in the case of Great Above is 9.0. That’s his BSSI.

The p12 tables

The notable p12 sires listed in the two tables, one table in alphabetical order and the other in rank order by BSSI, 1) were born during the period 1965-1985, 2) sired the dams of at least five stakes-siring stallions, and 3) have a BSSI of at least 9.0. We stipulate, first of all, that, while the BSSI is an efficient way of compiling a list of notable p12 sires, it is not a particularly precise measure of their effectivness as such because it is so readily subject to distortion.

For example, the sire Miswaki is p12 to major sires Galileo, Hernando, Dr. Fong, and 17 other sires of stakes winners. Those 20 sires are accountable for an aggregate of 362 stakes winners, yielding a BSSI of 18.1 for Miswaki. Top Ville, by comparison, has the higher BSSI of 20.56, based on six stakes-siring p12 descendants, including deceased world-class sire Montjeu, whose 113 stakes winners to date unwarrantably inflate Top Ville’s BSSI. Clearly, after considering the facts in the case, any reasonable observer would conclude that Miswaki is the better p12 sire. A practical assessment of a p12 sire requires a consideration of those facts.

This is why for each p12 sire listed in our tables, we show the number of stakes-siring p12 descendants, their aggregate number of stakes winners, and the names of those p12 descendant sires, listed in order of their contribution to aggregate stakes production. Keep in mind, though, that, because we are technically limited to a field width of only 254 characters, the list of sires out of daughters of some of the more prolific p12 sires must be left incomplete.

Notwithstanding our demurrer about the accuracty of the BSSI itself, the whole contents of the tables provide a template for your own assessment of the possible p12 effect relating to young, unproven stallions. And we would hasten to point out that the most current information is available at any time by reasonably priced subscription to our eCompuSire facility, which is accessible at our eNicks.com website. One of its featured search functions lists stakes winners with up to four ancestors in specific pedigree positions. All of the information shown in the tables, and more, can be obtained for a p12 sire by entering his name in position 12 of the ancestry template.

Position 12 and position 5

In the diagram above, the broodmare sire of the new individual is located at p5. It is reasonable to ask whether or not there is any real difference between an ancestor’s function at p5 and his function at p12. In other words, wouldn’t the best broodmare sires also be the best broodmare sires of sires? Does p12 really have a specialized function of its own? The answer, emphatically, is that, while good p12 sires do in fact rise from the ranks of the good p5 sires, only certain of those p5 sires also function well at p12.

The sire Key to the Mint provides especially convincing evidence of this. He was good enough as a broodmare sire (p5) to have been represented by 30 stakes-siring p12 descendants. Nevertheless, given all of that opportunity, he is represented by not a single major sire, and, accordingly, his BSSI is only 4.53. Success as a p5 influence does not assure success as a p12 influence.

Career factors

A correct assessment of p12 influence also depends upon a consideration of a sire’s long-term, career trajectory. Keep in mind that it might take 30 years, or more, from a sire’s birth for his p12 expression to peak. Our tables list sires born no later than 1985, but in certain cases even 30 years might not be long enough. Ahonoora, born in 1976 and p12 to important sires Cape Cross, Danasinga, Bletchley Park, Acclamation, Shinko Forest, New Approach, and Leroidesanimaux, is clearly an important p12 sire, but he might have gone unnoticed as such even as late as 2005 because he was not highly respected at stud until his early crops had raced. Mr. Prospector, at first standing in Florida, also had to prove himself worthy in order to attract mares whose daughters could be good enough to make him an important p12 sire. Sires that lack the advantage of a fast start take longer to express their p12 influence.

So much the worse is it for sires that have become important p5 sires only in recent years. A.P. Indy, born in 1989, is p12 to seven stakes-siring sires so far. The prospect of his ample opportunity as a p12 influence is assured by his overall reputation as a sire and his excellent performance thus far as a p5 sire (broodmare sire of 14 G1 winners). At this point, with Super Saver, Brethren, Morning Line, Dunkirk, and others waiting to make their mark, it would be a mistake to judge young, unproven sires out of his daughters on the basis of his current BSSI of only 5.0.

While there is much to consider when assessing p12 influence, in some cases the answer is simple. When a young, unproven stallion qualifies in other respects for success at stud–at whatever level–and is out of a mare whose sire is already p12 to at least one major, world-class sire, that stallion has an edge over many others you might choose for your mare.

Finally, though, so as not to overplay this factor, p12 influence is only one of four important factors. Many stallions with inferior p12 influence find a level of utility that is acceptable to a sufficient number of breeders, just as do stallions with superior p12 influence. Nevertheless, breeders would not consider a young, unproven sire for their mares or purchase his offspring without good reason to think he will sustain or rise above the level of anticipated utility at which he begins his stud career. That’s where the p12 factor comes into play.

Posted by Roger Lyons on Saturday, July 5, 2014 at 4:41 pm.

• Permalink • Comments Off on Notable Broodmare Sires of Sires

What are GeoNicks?

by Roger Lyons

As the world of thoroughbred breeding becomes increasingly globalized–with the increasing movement of breeding stock between North America, Europe, and Australasia–there remains the important sense in which all racing is local. It derives from the persistent fact that the horses must gather in one place to compete.

As a market structure, globalization doesn’t change that essential fact; therefore, the ability to correlate pedigree with geography becomes all the more important, and, although More Than Ready, for example, may sire stakes winners in North America and Australasia (but not so much in Europe), do the pedigrees of his stakes-winning offspring have commonalities between geographic regions or not?

That larger question aside, you need to know, as a breeder, whether or not the cross is performing as well in your region of interest as it’s performing globally, and that’s where GeoNicks enter the picture.

GeoNicks address the important question how a given pedigree cross has performed, comparatively, in the three major racing environments–North America, Europe, and Australasia. Just as the Werk Nick Rating, as featured at WTC’s online eNicks pedigree service, measures the effectiveness of crosses within the global population of stakes winners, GeoNicks measure those same crosses within the more limited stakes populations of those three respective racing environments. Thus, GeoNicks bring a geographic perspective to the evaluation of sire-line crosses.

As a supplement to the long-established Werk Nick Rating, GeoNicks reports include the regional letter-grade rating for the cross requested, the variant on which the grade is based, and a list of the stakes winners bred from the cross–but only the winners of stakes races run in the requested region (see sample reports–North America, Europe, Australasia).

GeoNicks does not replace the global Werk Nick Rating on which the thoroughbred industry has relied for the last 20 years. Breeders, buyers, and eNicks stallion sponsors are assured that the Werk Nick Rating will continue to be the centerpiece of WTC’s online pedigree service, eNicks.com. The GeoNicks options are provided as a supplemental service, currently available at promotional pricing–only at eNicks.com.

Werk Nick Rating(R), GeoNicks(TM), and eNicks(R) are trademarks of Werk Thoroughbred Consultants, Inc. Roger Lyons has been involved in the development and maintenance of WTC’s nick rating products for many years, participated in the development of GeoNicks(TM), and benefits materially from sales relating to those products.

Posted by Roger Lyons on Thursday, September 8, 2011 at 7:22 pm.

• Permalink • Comments Off on What are GeoNicks?

Ruler on Ice, Slop, Whatever

by Roger Lyons

Ruler on Ice, the horse that beat Shackleford at his own game in the Belmont slop, might not have been put to his highest and best use when he appeared to close well in the Sunland Derby (G3) to finish one-and-a-quarter lengths behind Twice the Appeal. That must have left the impression that he’s a closer because he was taken even farther back in the Frederico Tesio, came up two lengths short at the finish, and, really, was cruising, rather than closing.

The sloppy track notwithstanding, his Belmont effort suggests Ruler on Ice has more in common with Shackleford than with the closers in the race, most of which faded. I have to admit, he had me fooled. I dismissed him because he’s out of a Saratoga Six mare, and, in doing so, I missed the point entirely.

Several years ago I began to notice that quite a number of sires were getting stakes winners out of mares that had Saratoga Six either as their sire or broodmare sire–all from very slight opportunity. To take that as a suggestion of his quality as a broodmare sire doesn’t go quite far enough. After all, recognition of a good broodmare sire can arise from an ability to contribute quality to the foals of a limited range of sires or sire lines.

What distinguishes Saratoga Six as an ancestor of broodmares is his ability to contribute quality to the foals of a wide range of sires and sire lines. In short, he’s a good mixer. What he adds to the mix is suggested by the 7.4-furlong average stakes-winning distance of horses aged three and older out of his daughters. Ordinarily, the mode (most frequently occurring) distance more accurately captures central tendency as to distance than the average or median, but not in the case of Saratoga Six as a broodmare sire. Offspring of his daughters win stakes going six, seven, eight, and 8.5 furlongs at nearly equal frequencies.

Which is to say that he consistently passes on speed through his daughters, and it’s delivered in packages that tend to be exploitable by a wide range of stallions. Considering the wide range of sires that are represented by stakes winners out of mares with Saratoga Six in their ancestries (which you can look up yourself if you subscribe to CompuSire online), the frequency of graded/group stakes winners is creditable enough–11.3% G1 winners, 22.7% G1-2 winners, 37.5% G1-3 winners.

What I couldn’t imagine is that Ruler on Ice could stay–and I use that word advisedly–the Belmont distance of 12 furlongs. I have to think that says more about his sire Roman Ruler than about his broodmare sire, but there can be no doubt that the running style he’s discovered is just what Saratoga Six had in mind for him.

That’s where the parallel with Shackleford breaks down. It’s obvious that Shackleford gets speed from his sire and the ability to carry it from his dam. For Ruler on Ice it’s the other way around. In any event, it’s been a good year so far for horses that can do it that way.

Posted by Roger Lyons on Monday, June 13, 2011 at 6:54 am.

The Best Nick in the Belmont

by Roger Lyons

Master of Hounds (Kingmambo-Silk and Scarlet, by Sadler’s Wells) makes his third start of the year in the Belmont on Saturday, following his fifth-place finish in the Kentuck Derby, so he’s a relatively fresh horse, and he apparently travels well. So does his breeding.

His sire, Kingmambo, has at least one foal from each of 65 mares by Sadler’s Wells, and eight of those mares produced superior runners by him. It’s a simple nick to be sure, but it’s also very special. Besides Master of Hounds, that cross has yielded six G1 winners, including El Condor Pasa, Divine Proportions, Virginia Waters, Henrythenavigator, Thewayyouare, and Campanologist.

An actual cross is never quite as simple as its simple nick, which is why I like to consider a sire’s record with all of the potentially effective influences–for better or worse–that comprise a mare’s ancestry. That means compiling the sire’s superior-runner strike rates with all individual ancestors within six generations of the dam. On that basis, appropriate applications of the nick can be separated from those that are not.

With respect to Kingmambo’s record, the ancestry of Master of Hounds’ dam is all good. Through his 2008 crop Kingmambo has sired foals out of 48 mares with Lyphard in their ancestries–that’s her broodmare sire–and six of those mares produced stakes winners. The sire of her second dam is Irish River, with which Kingmambo has a strike rate of 2/20, one of those two being the dam of Master of Hounds. The other one was Sequoyah, also by Sadler’s Wells and the dam of both Henrythenavigator (G1) and Queen Cleopatra (G3).

That strike rate of 2/20 doesn’t seem encouraging until you consider the bigger picture. Kingmambo has sired foals out of only four mares that had both Sadler’s Wells and Irish River in their ancestries. Two of those mares account for Master of Hounds and two graded stakes winners, including the best one that’s come from the cross–Henrythenavigator. Thus, the strike rate of 2/20 can be reduced to 2/4.

Master of Hounds’ breeding doesn’t say definitively that he can handle the Belmont distance of 12 furlongs, but it’s not beyond the cross. El Condor Pasa and Companologist both won G1 races at that distance. He may not win, but Jackie and I aren’t going to let him take down our Belmont super.

Posted by Roger Lyons on Thursday, June 9, 2011 at 10:37 am.

• Permalink • Comments Off on The Best Nick in the Belmont

Dancing Rain ‘Not Guilty’ in Oaks Win

by Roger Lyons

If the expression “stole the race” is worth using at all, then it needs to be used less often than it is. First of all, stealing a race must involve an element of guile. A horse goes off at 20-1–kind of like Dancing Rain (Danehill Dancer-Rain Flower, by Indian Ridge, by Ahonoora) in the 12-furlong Epsom Oaks (G1)–and gets an easy lead. The soon-to-be losing jockeys are not that concerned, even though they’d prefer an “honest pace,” because they think she’ll be finished in any event by the time they’re coming off the turn. The soon-to-be winning jockey knows better, and that’s the con.

But, as W.C. Fields said, “you can’t cheat an honest man,” which in this context means that Dancing Rain could have stolen the Epsom Oaks only if there had been another filly (a mark) in the race better than she was. If the best horse wins, it’s not stealing, no matter how the race is run.

Anyone who thinks, as the T.V. analysts do, that there are just two kinds of horses, the front-runners and the closers, might well think Dancing Rain stole the Oaks. Because two horses were running more or less side by side in the lead during the early fractions of the Preakness, lots of people thought it was a speed duel. They entirely missed the point that one of those two horses–namely, Shackleford–is a stayer. Apparently, the concept of a horse that stays, that controls the pace and carries its speed around two turns, is too complex for network coverage.

Dancing Rain’s ability to show speed that stays is easy to figure out. The offspring of both Danehill Dancer (her sire) and Indian Ridge (her broodmare sire) have a mode (most frequently occurring) stakes-winning distance of eight furlongs, and in both cases it’s a strong mode. Dancing Rain’s speed carries because her second dam is by Alleged, the mode stakes-winning distance of whose offspring is, by a very large margin, 12 furlongs.

Not just any speed and stamina can combine effectively to yield a stayer, but this does. Danehill Dancer has a superior-runner strike rate of 7/42 with mares that have Alleged in their ancestries, and he has a strike rate of 6/28 when Alleged descends through a daughter, as in this case.

That daughter, Rose of Jericho, figures in the ancestry of another stakes winner by Danehill Dancer and in a revealing way. Dual-listed stakes winner Deauville Vision is out of a mare by Epsom Derby winner, Dr Devious. Like Indian Ridge, Dr Devious is by Ahonoora, but his dam is Rose of Jericho. So, Dancing Rain’s dam is a three-quarters sister to Deauville Vision’s broodmare sire. It’s the Ahonoora-Alleged sire-line cross through the same daughter of Alleged. Deauville Vision won listed stakes in Ireland at eight furlongs and 10 furlongs, at ages four and six, respectively.

Her pedigree says Dancing Rain is a stayer, and stayers don’t steal races. What could be more honest than a horse that goes to the front and stays there?

Posted by Roger Lyons on Saturday, June 4, 2011 at 11:03 am.

Stallion Selection Matters

by Roger Lyons

Bethany (Dayjur-Willamae, by Tentam), the dam of Met Mile (G1) winner Tizway, had good reasons for failing to produce a foal of any merit until her sixth season as a broodmare–I mean, besides her body refusing to cooperate in her fourth and fifth seasons. Or maybe she was trying to say she didn’t like the stallions she’d been bred to previously.

In retrospect, it’s clear she was bred beneath her station in 1998 when she conceived a foal by Benny the Dip. Seeking the Gold, sire of her 2000 and 2001 foals was her equal, more or less, but he lacked the commitment she required. Bethany is by Dayjur, whose broodmare sire is Mr. Prospector, and Seeking the Gold really didn’t want a foal inbred to his sire. Of the 24 mares he’d tried that with lifetime, only two produced stakes winners by him.

Finally, when bred to Capote, she had a chance with a sire that could have some affection for her. He didn’t like Danzig line much, but he was 3/8 with Tentam, sire of her dam, and 4/27 with Hoist the Flag, sire of her second dam. Not only did Bethany produce listed stakes winner Ticket to Seattle by Capote, but so did her half-sister, Ms. Teak Wood, the dam of Acceptable (G3). Bethany wasn’t the girl of his dreams, but Capote liked her well enough.

Tiznow, sire of Tizway, went downright goofy over her, and it was her speed. Her sire, Dayjur, was a Champion sprinter, and her broodmare sire Tentam was out of Tamerett, the second dam of Gone West. If a mare contributes the speed required to control or press the pace, then Tiznow will contribute the ability to carry that speed as far as it deserves to go. Tizway resulted from a match made in heaven.

Then Bethany went stone cold the next two years when bred to Gulch in 2005 and then to Aldebaran the next year. Lifetime, Gulch went 0/5 with Dayjur, 0/6 with Tentam, and only 1/48 with Mr. Prospector. Seeking the Gold, Gulch, Aldebaran–what difference could it possibly make? They’re all by Mr. Prospector!

Then, after a 2008 unraced foal by Vindication, she slipped in 2009, produced a 2010 foal by Elusive Quality, and that year went back to Tiznow. The good news, besides her second chance with Tiznow, is that Elusive Quality, by Gone West, by Mr. Prospector, is 3/10 with Dayjur–3/8 with daughters of Dayjur, including G1 winner Elusive City.

I’ve written in the past about how well daughters of Dayjur buffer inbreeding to Mr. Prospector, but every good thing has its limits. The lesson here is that, if the inbreeding notation on your pedigree printout says 2 x whatever, then just try something else.

Posted by Roger Lyons on Wednesday, June 1, 2011 at 6:46 am.

• Permalink • Comments Off on Stallion Selection Matters