By Frances J. Karon

The Derby walkover began at 6:14 PM. O Besos, a chestnut son of 2013 Kentucky Derby winner Orb, was the first to leave the chute, accompanied by his connections. Somewhere in that group leading the way was the colt’s breeder, co-owner L. Barrett Bernard, who had tucked a memento, given to him by his nephew Jon-Brent, into his inside coat pocket earlier that day.

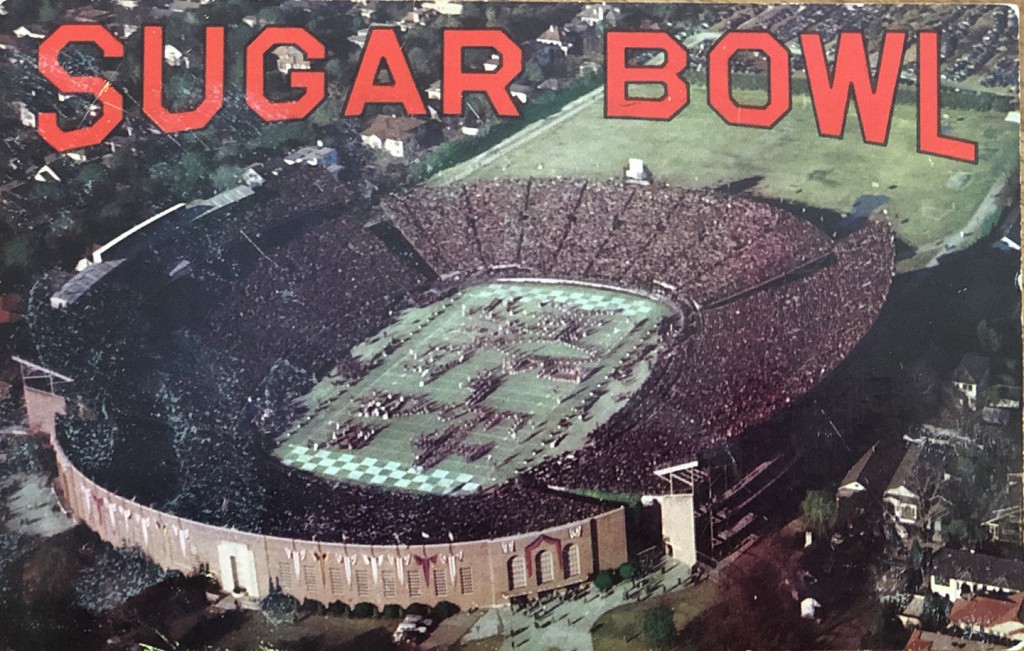

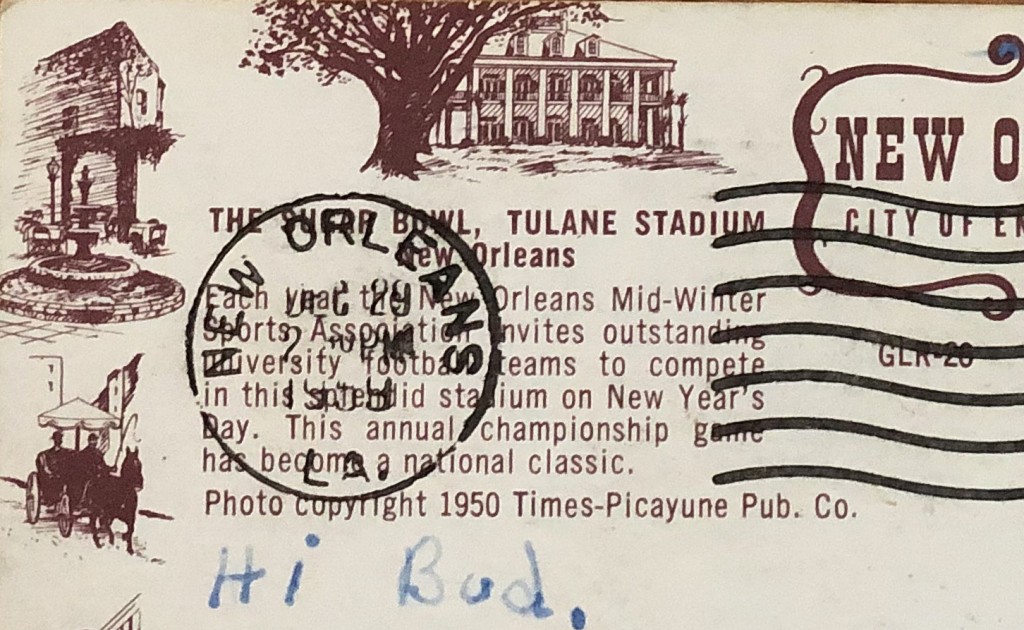

It was a postcard, an aerial photograph of Tulane Stadium printed with “SUGAR BOWL†– the stadium’s nickname – in big red letters at the top, mailed from New Orleans, Louisiana, on December 29th, 1959. A $0.03 Statue of Liberty stamp had been canceled by the U.S. Post Office at a partially illegible time in the two o’clock hour of the afternoon.

The recipient’s address was vague: “Russell Springs, Ky.†– you used to be able to do that for small towns out in the country – and it had been sent to “Mr. Barrett Bernard.â€

In a neatly written, faded blue script, it read:

“Hi Bud,

This a big football field, isn’t it? Be watching the game on T.V. I’ll be there someplace. I wish you could see it. Maybe someday, huh? I hope so.Â

Love,

Brentleyâ€

With the postcard safely, or so he thought, placed in his pocket, Barrett Bernard, along with his family, walked from trainer Greg Foley’s barn to the chute, and then, starting at 6:14, he wended his way around the first turn, through the tunnel, and into the paddock with his first-ever Kentucky Derby starter.

Eighteen other horses followed the O Besos entourage from the backside to the saddling paddock. There were so many people on the racetrack – trainers, staff, owners, family, and friends – that they and the horses were spread almost all the way across its width, from one rail to the other.

Soup and Sandwich was the last to leave the holding area. It was in his wake, after the other 3-year-olds, pony horses, and hundreds of people had crossed, that Brentley’s postcard was spotted laying in the dirt on the bend of the turn, towards the inside rail. If not for the bright red “Sugar Bowl†lettering, it might never have been noticed where it had fallen and would soon have been buried or torn to shreds by the tractors harrowing the dirt and then by the Kentucky Derby field running over it.

When I found it there, I picked it up without looking closely, with the notion of throwing it away at the first opportunity. It was a piece of litter, I thought, that had blown onto the track on a very windy day.

I didn’t immediately pay much attention to it. Soup and Sandwich was on edge, lashing out occasionally with his hind legs, so I kept watching him, wanting to be ready with my camera if he kicked again. But my mind kept going back to what I held in my hand. It didn’t feel like the usual trash that you find on the track, so with one eye on Soup and Sandwich’s rear end, I turned the card over and read the note that ended with, “Love, Brentley.â€

It was clear that somebody up ahead would be missing that postcard very much.

The next morning, I uploaded front and back photographs of it on Twitter, hoping someone would know who had lost it. With a quick search, one of my followers, Nicole Proulx, solved the mystery, which ended up not being so mysterious after all: the addressee, Mr. (now Dr.) Barrett Bernard, was the breeder of O Besos.

Sixty-one years ago, Brentley, Barrett’s older brother, was on the Western Kentucky University Hilltoppers’ basketball team that had traveled to New Orleans for the Sugar Bowl basketball tournament, held in conjunction with the Sugar Bowl football game. The Hilltoppers won the tournament, getting the title over Tulane by 71-67 on December 30th, 1959.

That date, a Wednesday, was one day after 19-year-old Brentley had sent Barrett the postcard token of his time in NOLA, a city filled with the big dreams and wide-eyed wonder of a college student thinking of his kid brother back home. The Sugar Bowl football game that Brentley attended on New Year’s Day had a crowd size of almost 75 times the population of Russell Springs, which was 1,125 during the 1960 census.

Life went on, and the Bernards grew up. Brentley graduated from WKU, joined the Air Force, and received degrees in dentistry and later orthodontics from the University of Louisville. Barrett likewise went to U of L thinking he, too, would go into dentistry, but instead veered towards a medical degree, and the brothers from tiny Russell Springs, where they used to ride the Tennessee Walking horses on their parents’ farm, forged ahead with their medical careers and their lives, getting married and having families of two sons each.

By then, the old Tulane Stadium had been torn down, and the Sugar Bowl postcard was long forgotten.

The Bernards ventured into racehorse ownership, too – Brentley first, joining a group put together by Burk Kessinger Jr. Barrett followed in the footsteps of his “role model†older brother, becoming involved in a partnership formed by John A. Bell of Jonabell Farm, with Shug McGaughey as trainer. Barrett eventually bought a horse himself, an unraced 2-year-old, for $13,000 at the 2000 Keeneland November sale. Named Silver Tie Lady, the Black Tie Affair filly won twice before she was claimed. Her final win for Barrett’s Silver Tie Racing partnership came at Churchill Downs one month before Brentley died, aged 60, in June of 2001, after a battle with scleroderma, a painful and debilitating disease that affected his work as an oral maxillofacial surgeon, and a “hypertensive crisis†that led to kidney damage.

After what Barrett describes as a “dreadful three years,†which included a great deal of time the brothers spent together in other doctors’ offices and hospitals like Johns Hopkins and the Mayo Clinic, Barrett sadly felt a sort of “peace†for his brother when Brentley passed away before his time.

“I’ve seen a lot of terrible stuff as an emergency room doctor,†Barrett said. “But I feel tender when I think about my brother.â€

So when, on the morning of O Besos’s Kentucky Derby, Barrett’s nephew gave him the old postcard he’d found in storage, he was touched. “I’m not superstitious but I thought it was a good omen,†Barrett said. “It really meant the world to me, and I put it in my pocket. Knowing how he liked horses and having his sons there [at the Derby] with me, I know he would have loved all of it.â€

Amid the chaos, Barrett didn’t realize until later that evening, long after O Besos had crossed the wire fifth at 41-1, that he’d lost the postcard, and he was devastated when he thought it was gone forever. Of course, it wasn’t, and he got it back the week after the race. “It will never get lost again,†he said, incredulous that it hadn’t been trampled by any of the horses or many people walking behind him.

“Why wasn’t it damaged? You’ve just got to believe there’s somebody in control,†he said. “I’ve been blessed. I’ve always said that there’s an angel sitting on my shoulder, and I really believe that.â€

Dr. Brentley Bernard may not have physically been at Churchill on the day his brother ran a horse in the Derby but he was every bit there in spirit, and so here’s to all the much-missed Brentley Bernards of the world whose stories we don’t know but who are carried in the minds, hearts – and sometimes pockets – of their loved ones.

The words of a 19-year-old to his 10-year-old brother foreshadowed how Barrett might have felt about making it to the Derby without Brentley: “I’ll be there someplace. I wish you could see it. Maybe someday, huh? I hope so.â€